Harry’s Guide to: MM6

Everything you need to know MM6, the more casual counterpart to Maison Margiela’s luxurious ethos.

Radical ideas, whether in politics, architecture, or fashion, are often misunderstood before they’re accepted. Consider Maison Martin Margiela (now Maison Margiela), the house that introduced new concepts—deconstructing clothing to its bare essentials, subverting luxury, and subverting clothing itself—and radical new styles in its early seasons. At the time, these things were met with disdain. Generations later, the work’s been so undeniable that it can weather any designer.

“Everyone is influenced by Comme des Garçons and by Martin Margiela,” said Marc Jacobs in 2008. Or, at least, designers. At the onset, in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, the house’s distinctive approach earned some grumbling from fashion’s permanent class. Clothes were beautiful and expressive, but shows were held in out-of-the-way neighbourhoods, and the house was hard to contact for information or quotes. As late as a decade in, there was even some trepidation about Margiela’s would-be radical influence on Hermès in advance of his hiring. These days, Margiela’s ideas are so central to—and so subsumed by—fashion that the chafing is hard to picture. That place comes from a set of ideas the house laid down early, massive enough to last for decades, and new enough, then, to bring out some vitriol.

The story starts, definitively, with Margiela. Born in 1957 in Genk, Belgium, he knew early on that he wanted to design, and sewed clothes for his dolls as a kid—using his mother’s machine—before arriving at Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts in the ‘70s. After graduation, he worked under Jean Paul Gaultier, in Paris, for a few seasons. He founded his namesake line, with partner Jenny Meriens, in 1988.

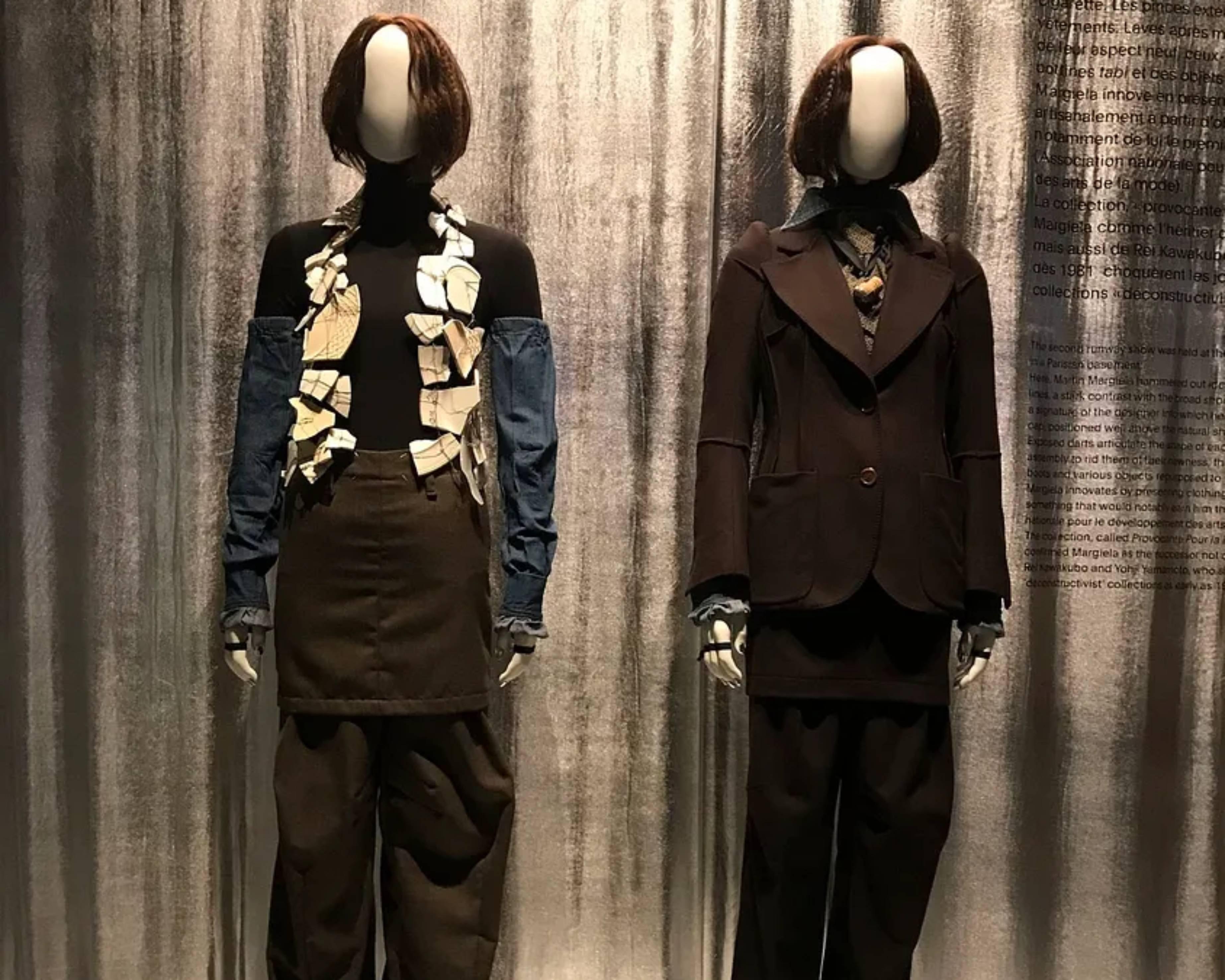

MM6’s first few years there read like a highlight reel or a bomb blast: one house in Paris, singlehandedly changing everything. In short, under Margiela, the whole concept of clothing was upended. Cheap—or even scrap—material was heightened to luxury, and sometimes vice-versa; labels and styling were thrown on their ear; colour was thrown into question. On a needles-and-pins level, the house put out as many good clothes as it did good ideas. (Personal favourites include the ‘89 A/W collection, which featured a vest made of cracked-up porcelain, a perfect patchwork shearling coat and a three-piece pantsuit, and 1993 S/S, which featured reworked theatre costumes.) Somewhere in the mix, he introduced the Tabi shoe, the cigarette shoulder, and probably invented upcycling.

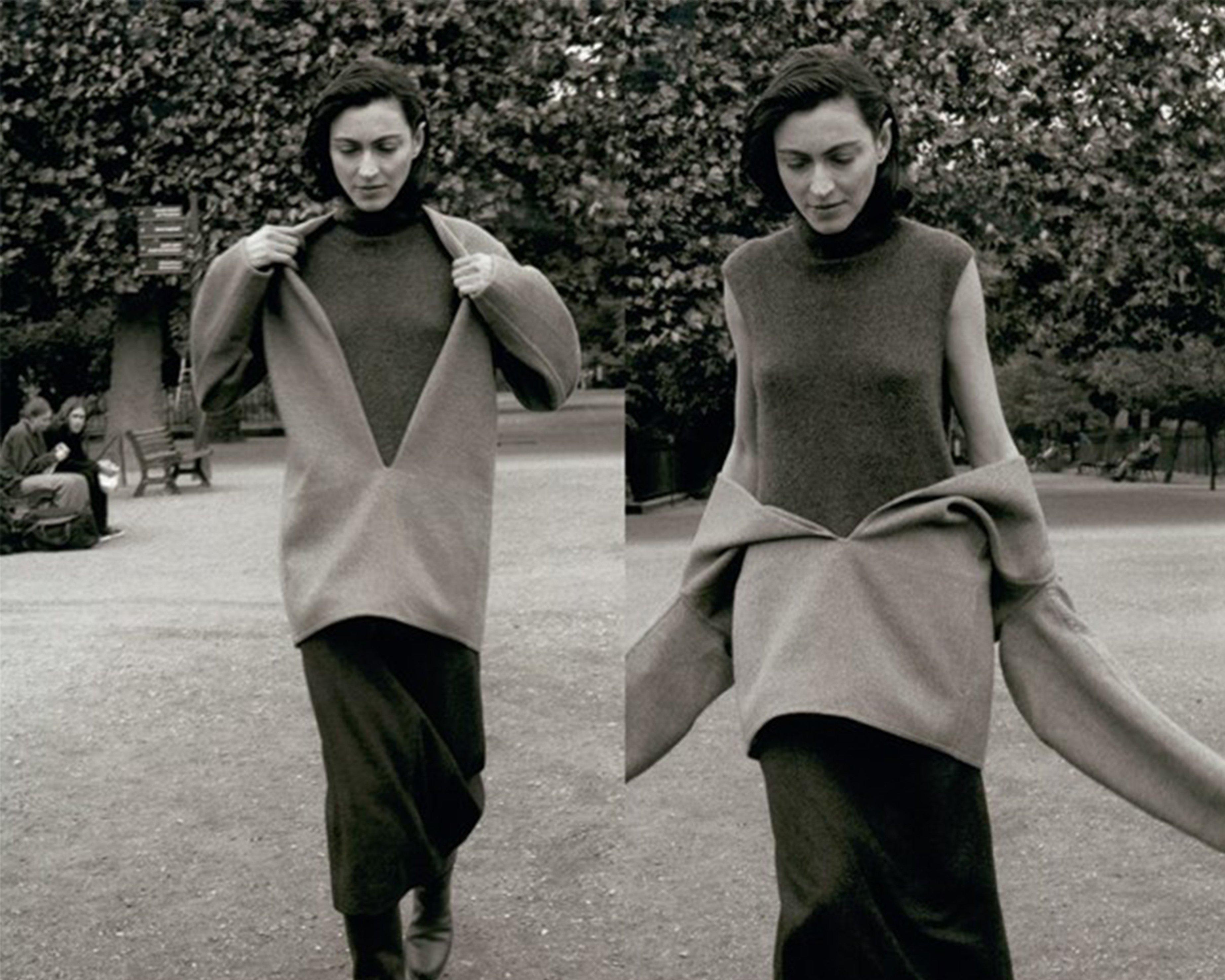

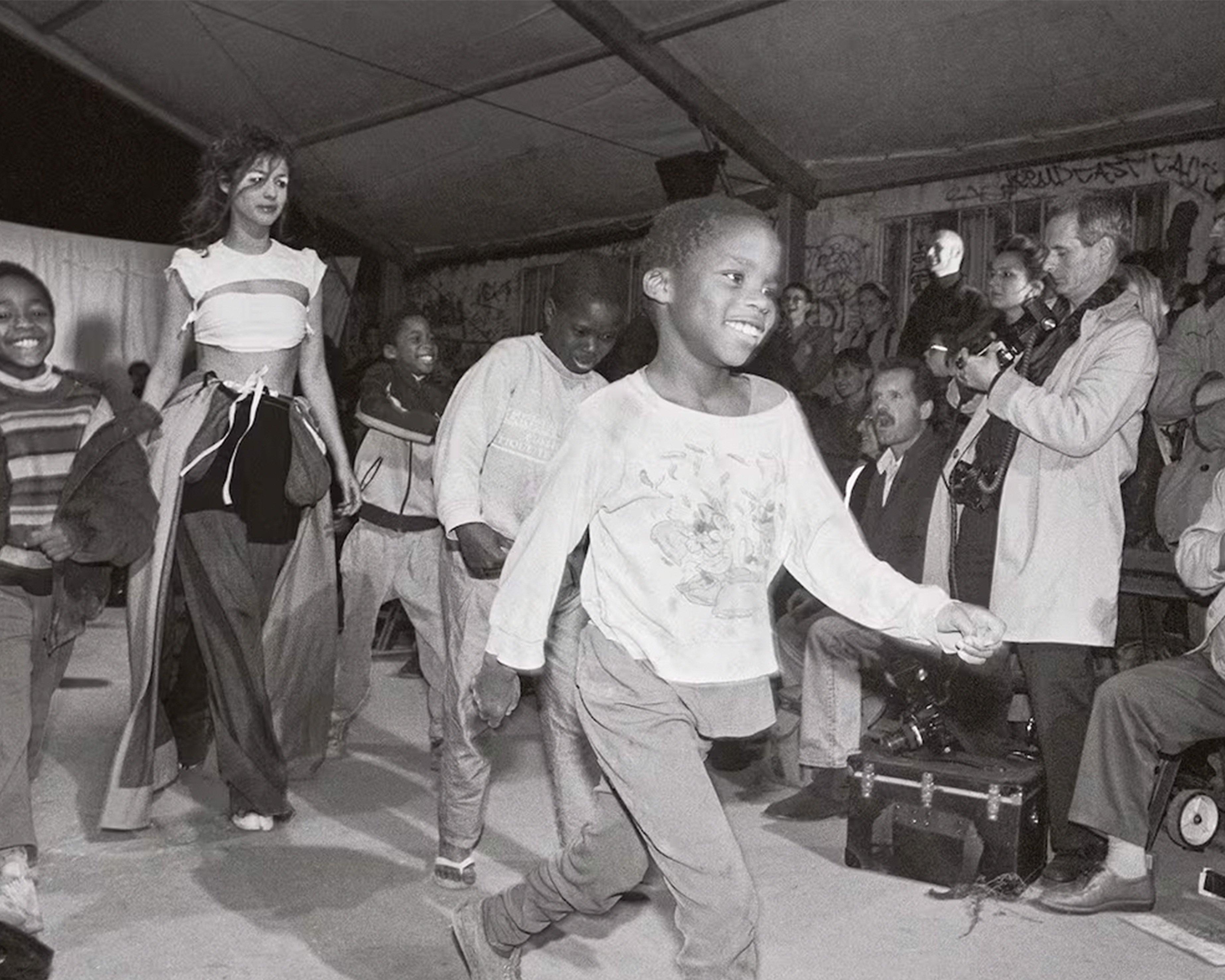

Along with the clothes came ideas. Shows were held on freight trains and school playgrounds, far from Paris’ center. Models’ faces would be hidden behind masks; clothes would sometimes have garish proportions. Over Margiela’s two decades at the helm, work followed several themes. Items were “deconstructed”—taken apart and rebuilt; clothes about clothes, which lay bare the seams. Items were repurposed—a stockman dress as an old jacket; a plastic as a gown—and clothing was meant to degrade. It was clothing commenting or other clothing—or, maybe, an expression of Margiela’s skill.

Margiela’s team was composed of anonymous young designers who all worked in white lab coats and got a sort of fashion PhD. In 1997, Margiela took over as creative director of Hermès, making muted, considered garments there, and expanded his own line that year. MMM grew conceptually, introducing its anonymous tag—a series of numbers, not really explained—to determine the brand’s footprint. It included a couture line, fragrances, menswear and MM6, then a diffusion line, originally female, and then called Line 6.

In 2009 Margiela left, announcing his exit by fax. A few years later, in 2014, John Galliano took over. It seemed at first a tricky hire: Galliano, the old head of Givenchy and then Dior, was a designer of entirely different aesthetic and social comportment from Margiela. Galliano, who left his job in 2011 after an exculpatory incident, was a public designer—in many ways a celebrity—making clothing decidedly more showy and extravagant than Margiela had done. But in all the big ways, what he’s done at Margiela has worked, and in many ways, because of MM6.

When the two met, shortly after Galliano’s hiring, in 2016, Margiela told him to take the brand’s DNA, protect himself, and go into the future. Galliano did, splitting Margiela’s aesthetic into two distinct directions, Margiela itself and MM6. Items Galliano designs for the Maison fit between his own breadth of influences and the line’s keen conceptual framework; the work from MM6 hews more closely to Margiela’s original aesthetic while expanding its reach.

As Galliano burnished Margiela’s namesake and couture line—a show in January for the latter was the most memorable couture show in years—with a series of improving collections, MM6 has grown deeply itself, expanding Margiela’s original conceptual and aesthetic ideals from his most productive periods. Originally conceived as a simpler, but still avant-garde continuation of Margiela, MM6 has grown and become the old work’s new standard bearer. The brand went gender-neutral a few years ago—bigger sizes and silhouettes—and has since expanded its footprint. Many archival items are in direct conversation with the archive—a 5-zip biker jacket, redone in nylon, some in leather—but are pretty current and wearable. They’ve also dipped into collaborations. A 2020 collab with The North Face, rearranged the Denali parka into something avant-garde and expressive, while a recent collaboration with Supreme placed Galliano and Margiela’s ideas into a universal, casual context.

MMM’s rumination on Margiela’s early work makes clear how much the two designers share: Margiela’s upcycling and simplicity aren’t far off from the dresses in Galliano’s first show in Paris, his F/W ‘94-’95 collection, where Ingrid Sischy wrote, “he pulled off the entire show with basic rolls of black fabric, using both the matte and the shiny sides.” Or, how about Margiela now and then cutting items along the bias, which was Galliano’s signature. Each’s work is ruled by emotion: Margiela, with his muted expressions of beauty, chooses restraint; Galliano, centring sexuality, is effusive. Each’s clothes also just comment on other clothes. Old Margiela’s deconstructions of fashion were direct and pared-down, expressed over decades and in numerous collections, while Galliano’s exaggerated and ornate commentary focuses on an item and gilds it. The simple math here is that they’re two geniuses, and the ideas that Margiela put down decades ago, in his golden era, remain fresh enough to both take on Galliano, refresh themselves, and expand, under MM6, a brand that is long past being misunderstood.

Sami Reiss is a writer from Ottawa, Ont., who lives in Carroll Gardens. His newsletter, Snake, covers design. He writes on this topic and others for GQ, The Wall St. Journal, ESPN, Ssense, Dwell, and consults.